Mitsubishi Heavy Industries

MHI is a vital Japanese defense, shipbuilding and energy company. It plays a crucial role in arming Western militaries and powering growing energy demand.

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) is one of the core groups of Mitsubishi, a Japanese conglomerate that still builds many of the pillars of a modern advanced economy. Although they share a name with MUJF and Mitsubishi Corporation, they are not jointly owned or operated. Despite the founding family being stripped of its ownership after the conclusion of the Second World War and the company being broken up, MHI has managed to survive and now flourishes in producing gas turbines for electricity generation. MHI is also one of the leading pursuers of the Japanese goal of making hydrogen a core fuel source for industrial civilization. Although the dream of hydrogen displacing fossil fuels is unlikely, MHI will reap the benefits of growing energy demand from increased data center power demand and efforts across the Western world to electrify energy usage, as natural gas is the only realistic generation source that can be built quickly and without the intermittency problems of variable renewables.

Founded as a shipbuilding company, MHI continues to produce high-quality naval vessels for the Japanese Navy on budget, on time, and at far lower cost than comparable US vessels. As the largest defense manufacturer in Japan, MHI is key to Japan’s quiet efforts to expand its military forces and capabilities. Additionally, as the premier Japanese space company, building rockets and satellites and having a history of building civilian nuclear reactors, MHI is the prime candidate to develop a Japanese nuclear weapon program if a change in the security situation pushes Japan to change its policy, especially if war breaks out in the Taiwan Straits.

Defense

MHI played a significant role in arms manufacturing for the Japanese Empire during the Second World War, building the famous Zero A6M fighters for the Imperial Japanese Navy (Nakajima and Kawasaki primarily built aircraft for the Imperial Japanese Army; Japan did not have a dedicated air force in WW2) and the battleship Mushashi, which, along with her sister ship Yamato, were the largest class of battleships ever built. After the conclusion of the war, Mitsubishi was split into three companies. With the pacifist constitution enforced on the country by the United States, Mitsubishi’s defense-related manufacturing looked to be at an end. However, with the outbreak of the Korean War and the emergence of a communist threat to American allies in East Asia (namely the Soviet Union, China, and North Korea), Japan was allowed to expand its military capabilities under the guidance of American advisors and defense manufacturers. Japan would not be allowed to develop its own top-tier platforms but was allowed to build American planes, artillery pieces, tanks, and ships.

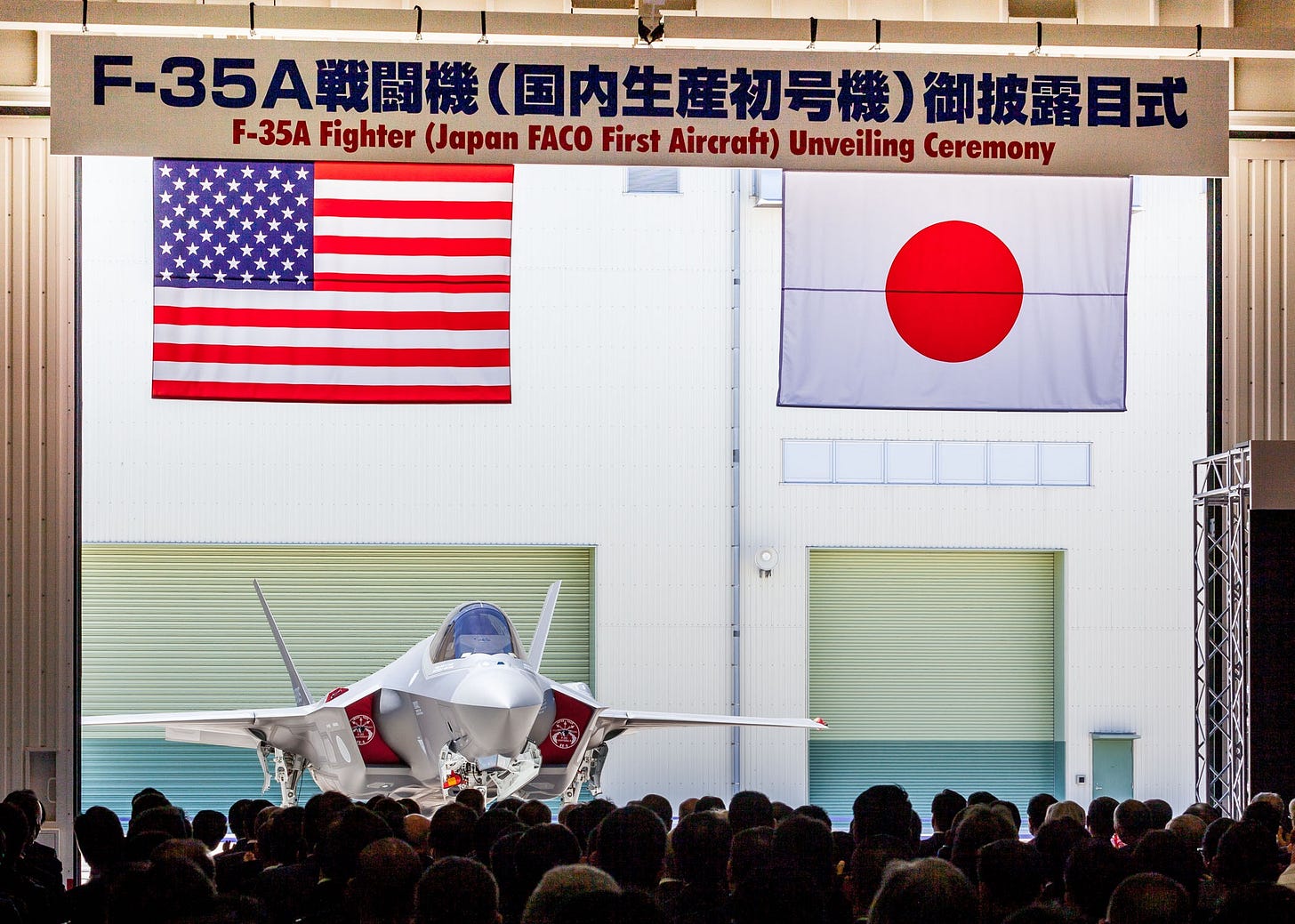

The first Japanese built F35-A fighter jet.

Until 2014, Japan restricted its military exports, limiting MHI's incentive to invest in developing military hardware as it could only sell to the Japanese Self-Defense Force (JSDF). Growing tensions have spurred two major policy changes in Japanese defense: the 2015 Legislation for Peace and Security allowed Japan to develop defensive capabilities concerning a foreign contingency, meaning Japan could begin to prepare for the fallout from a potential invasion of Taiwan and possibly support the US in intervening. In 2022, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Kishida administration released a series of national security strategy documents, including a plan for a defense build-up program and an ambition to raise defense spending to 2% of GDP by 2027 and giving Japan the third largest defense budget in the world. Although Japan has a history of limited exports and significant American arms purchases, MHI is well placed to take advantage of this increased funding, primarily spent on offensive missiles, air defense, and unmanned intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance drones. MHI will doubtless be contracted to build AEGIS-capable ships as the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) requirements increase from eight ships to ten (AEGIS is a missile defense system) and is already working on a new vertical launch missile system for the JMSDF. Japan’s defense build-up program will likely open up further opportunities for increased defense manufacturing for MHI, especially given the strain on the U.S. defense industrial base.

For Japan's air force, the Japanese Air Self Defense Force (JASDF), MHI built McDonnell Douglas F4 jets under license in the 1980s, F2 jets in the 1990s, and 213 F-15J air superiority fighters under license from Lockheed Martin from 1981. This partnership has continued, with MHI responsible for assembling 38 of the 42 F-35A fighters the JASDF has currently ordered. F35A fighters cost Japan an average of $82.5 million, with the acquisition program costing over $23 billion. This high cost is partly why Japan joined the United Kingdom and Italy in the development of the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP), a sixth-generation fighter jet also known as Tempest, as a cheaper alternative to the US Air Force’s Next Generation Air Dominance program. GCAP is designed to be less expensive and also ensure the UK, Japan, and Italy can continue domestically producing advanced fighter jets, as the US refused Japan access to its F-22 stealth fighter. The GCAP is scheduled to test a demonstrator in 2027. Although the exact workshare is not yet available, Japan is funding 40% of the development costs. MHI will likely lead Japanese involvement while BAE Systems coordinates the British effort. This also includes Rolls Royce, which will probably build engines for GCAP.

MHI is not assembling F35B short take-off and landing capable jets for the JMSDF, which are being purchased from Lockheed in the $23 billion F35 deal. These jets exemplify the JSDF's “speak softly and carry a big stick” doctrine. Although Japan has a pacifist constitution and its armed forces are described as self-defense forces, it has one of East Asia's largest and best-equipped militaries. The F35B variant is used by the British, Italian, and US Marine Corps to operate from aircraft carriers, which Japan officially do not possess. However, its Izumo class “Helicopter Destroyers” are aircraft carriers in all but name and are being adapted with more robust flight decks to operate F35B jets, giving the JMSDF two small aircraft carriers that can carry a total of 56 aircraft.

Along with Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Japan Marine United, and IHI Corporation, MHI is one of Japan's most important shipbuilders. Of the JMSDF’s 75 major surface vessels and submarines, MHI has built 21 ships and submarines. MHI is currently contracted to build Mogami-class frigates, at least one Taigei-class lithium-ion battery-powered attack submarine, and an AEGIS-equipped destroyer due for commissioning in 2027. By ordering ships of the same class from different manufacturers, the Japanese Ministry of Defense and JSDF ensure that skills and knowledge are not constrained to a single company that could go out of business, helping to build robustness into a defense industry that a lack of export opportunities has constrained. MHI civilian shipbuilding has suffered from the same pressures other Japanese and South Korean shipbuilders face as the China State Shipbuilding Corporation outcompetes them in construction speed and cost. Despite this, MHI still builds advanced ships, including LNG carriers and roll on roll off car carriers.

JS Mogami built by MHI in Nagasaki

MHI is also working on a deal to overhaul and repair US Navy ships based in the Pacific, as US shipyards have work backlogs over ten years. If successful, this may open up the possibility of MHI building ships for the US Navy, as MHI can build ships like the Kongo more quickly and cheaply than US shipbuilders, the Kongo being roughly equivalent to Arleigh Burke destroyers that are the mainstay of the US fleet. Unlike US shipbuilders, MHI (and others) bear financial penalties if ships are not delivered on time or over budget. Although this will face furious opposition from US shipbuilders, the scale and speed of the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s fleet expansion may give the US no choice but to buy from allies: thanks to the efforts of the China State Shipbuilding Corporation, China’s navy is now the largest in the world. This may not be as outlandish as it may seem, as MHI is one of only a few non-American companies trusted to build advanced US missile technology also capable of building ships. A potential starting point would be for the US to procure from MHI auxiliary ships that carry fuel and supplies and cancel the proposed Light Replenishment Oiler to free up US shipyard space for combat vessel production and maintenance.

MHI is the lead contractor for producing PAC3 Patriot missiles, currently building 30 missiles a year. Japan is the only country in the world aside from the US with this capability, but 18 countries worldwide currently use the Patriot system. Given the substantial threat posed by the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force and its arsenal of thousands of ballistic and cruise missiles, as well as Ukraine's current use of Patriot missiles to intercept Russian missile attacks, increasing the number of interceptors produced every year is vital for US and allied stockpiles. In the US, Raytheon and Lockheed Martin are aiming to increase production from 500 to 750 interceptors a year, and the US hopes MHI will be able to produce around 100 a year, but a shortage of components responsible for end-stage interception currently manufactured by Boeing is limiting this to 60 a year by 2027. With MHI’s technical expertise and US willingness to license overall missile production, it may be worthwhile to contract MHI to produce the components Boeing is struggling with.

MHI also produces the US-designed Standard Missile 3 (SM3) used by the JMSDF and US Navy to intercept ballistic missiles, the Type 12 anti-ship cruise missile, and the ASM-3 supersonic anti-ship missile. The US only produces 12 SM3 missiles annually and expended an entire year's worth of production in defending Israel against an Iranian ballistic missile attack in October 2024. MHI would be a natural option to increase the production of these crucial defensive weapons. As Japanese doctrine now allows the JSDF to possess offensive ballistic and cruise missiles to attack ground-based targets, the Japanese government would be wiser to use MHI to produce these capabilities rather than relying on strained American defense industrial capacity, especially as MHI has experience in building rockets for the Japanese space agency, JAXA.

MHI’s role in producing space rockets has not been trailblazing but rather reflects MHIs usual competence and diligence. It has successfully launched dozens of H-II rockets carrying civilian satellites into orbit. MHI’s rockets have also carried Information Gathering Satellites for the Japanese Cabinet’s Satellite Intelligence Center. MHI’s H3 rocket, which the company spent around $1.5 billion USD developing, failed on its first launch, but subsequent missions have been successful. Although the H3 is uncompetitive compared to SpaceX’s Falcon 9 regarding launch costs, JAXA hopes the cost per mission of the H3 will eventually settle at $50m, around $17 million less than SpaceX.

A H3 rocket lifting off from the Tanegashima Space Center in Feb 2024

Japan cannot realistically compete in building up as many offensive ballistic missiles as China currently possesses, but MHI is well placed to develop a limited offensive capability for the JSDF. As manufacturers of space rockets and ballistic missiles, in combination with enough stockpiled plutonium to build hundreds of nuclear weapons, MHI would be the natural option to develop a Japanese nuclear capability. Unlike South Korea, whose population supports the acquisition of nuclear weapons or hosting US warheads to defend from North Korean threats, the Japanese public is still very resistant to developing a nuclear capability. Public opinion may change if China was to successfully invade Taiwan. Japan, through MHI, has all the necessary technical expertise and components to develop nuclear weapons rapidly.

Increased defense spending by NATO countries who are seeking to rebuild their militaries after decades of underinvestment may be an opportunity for MHI to expand defense sales to countries that have previously bought from Western European or American companies, although the countries that are expanding the most, such as Poland, appear to be buying more from with South Korean companies. However, if MHI can build up offensive and defensive missile systems for the JSDF, it will be well-placed to expand its sales across the Western world. MHI’s defense business relationship with the Japanese state appears to be a healthy one. However, MHI’s attempt to develop commercial aircraft proves it cannot do everything the Japanese state aspires to.

Commercial Aerospace

MHI’s close relationship with the Japanese state, particularly the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), can come at a cost. More than 40 years after Japan last produced commercial aircraft, MHI's attempt to enter the commercial aerospace industry failed, with over 1 trillion yen ($6.5bn USD) spent over 15 years.

The results of European collaboration to produce Airbus yielded an enormous strategic asset. Breaking into the commercial aerospace industry dominated by Airbus and Boeing is a goal for China, Russia, and, until recently, Japan. More than 40 years after Japan last produced commercial aircraft, in 2002, METI launched a project to develop a small regional jet. The success of the Embraer 145 jet, developed in the late 1980s, had led to over 1200 orders and proved popular for regional airlines and larger carriers using them as short-haul aircraft, gutting the turboprop market that had previously served these routes. Rather than launching into a highly costly and competitive market for widebody aircraft, as Airbus had done when they launched the A300, METI envisioned a smaller, more scaleable project that could entice manufacturers rather than getting them to commit to taking on Boeing and Airbus directly.

In 2003, MHI dispatched a small team to the US to research the potential of a new jet ahead of a METI deadline to present proposals and win 25 billion yen in development funding. From November 2003, MHI began exhibiting smaller-scale models and internal mock-ups, with the concept growing larger and more ambitious with every air show, moving from 20 seats to 90 by the Paris Air Show in May 2005. While MHI continued to show its proposed jet at air shows and won orders from Japanese and foreign airlines, the slow development time and advances in engine technology from Rolls Royce, General Electric, and Pratt and Whitney meant MHI’s jet was soon outdated and less fuel efficient than other aircraft. It first flew in 2015 and began the lengthy flight testing process to secure a type certificate from the US Federal Air Administration that would allow the production and sale of the aircraft to carriers that flew inside the US. MHI underestimated the rigor required to acquire a type certificate, only beginning to hire engineers who understood the process in 2016 after flight testing had already begun. In 2020, MHI suspended the development of the aircraft (renamed the Spacejet in 2019) when it became clear that continued development would cost a minimum of 100 billion yen annually, and that they could not guarantee a delivery date.

Rather than continuing to develop an uncompetitive and costly aircraft, canceling the Spacejet shows autonomy from MHI with respect to Japanese government policy and was a sensible move for the company. It has not significantly affected the relationship with the government, which continues to rely on MHI to meet future Japanese energy needs.

Energy

Japan is almost totally reliant on imports of raw materials for industrial use and electricity production. In 2022, gas-fired power stations produced 332.6 GWh out of a total generation of 1012 GWh, or 32%. Unlike many European nations that have chosen to prioritize carbon emission reductions, in Japan, the importance of industrial production and the shutdown of most of the country's nuclear power stations after the 2011 Fukushima incident has meant that coal-fired power stations still fulfill 30% of generation needs. The Japanese government, aware of the global desire to reduce emissions and conscious that Japan depends on imports, has adopted an energy strategy to balance competing needs.

A MHI M501J Series Gas Turbine

Until the Fukushima incident in 2011, 33 nuclear power stations produced 30% of the country's electricity, and the government aimed for this to increase to 40% by 2030. MHI had built all of Japan’s operational Pressurised Water Reactors (PWRs) and was contracted to build two 1500 MWe Advanced PWRs, but this plan has been put to one side. In the aftermath of the tsunami and radiation leak, all of Japan's nuclear reactors were shut down indefinitely. In late 2024, 13 of Japan’s 25 nuclear power plants were operational. MHI is currently developing a 1200 MWe PWR called SRZ-1200 that it hopes to commercialize in the mid 2030s, meaning MHI may miss out on the current renewed enthusiasm for nuclear power driven by global energy security concerns.

After the Fukushima incident, Japan could have reevaluated its energy policy and turned towards intermittent renewables to secure its future energy needs. According to the Global Wind Energy Council, Japan has the potential for around 128 GW capacity for fixed bottom projects in shallow waters and 424 GW for floating offshore wind in deeper waters. As a major industrial company, MHI could have played a role in constructing wind turbines. Although Japan’s location at the heart of four tectonic plates and its vulnerability to earthquakes, tsunamis, and typhoons halted its proposed nuclear expansion, fortunately, Japan did not pursue offshore intermittent wind generation as this infrastructure would be incredibly vulnerable to natural disasters. Japan has also therefore avoided the significant hidden transmission and balancing costs of intermittent wind, which have contributed to increasing energy costs in Britain, Denmark, Texas, and Germany. Instead, the Japanese government reasserted its policy of pursuing carbon capture technology and the pursuit of “green hydrogen” as a fuel source, which MHI puts at the heart of its plans to help countries pursue a low-carbon generation future.

MHI's main revenues from its energy business come from selling turbines used in gas-fired power stations. In 2023, MHI Power Systems division was the global market leader in selling gas turbines, with a 36% market share, but they also sold 56% of the most advanced turbines, securing 120 orders for their latest JAC (J-Series Air-Cooled) model gas turbines in Brazil, Canada, Japan, Mexico, Peru, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, and the United States. These turbines have a shorter start-up time, can change their power output faster than previous models, and have higher efficiency. The greater the temperatures at which fuel can be combusted, the more efficient the turbine is at converting fuel to power. MHI’s 420MW turbines can also burn a mixture of hydrogen and natural gas, which burns at a higher temperature than solely using natural gas. To achieve these temperatures, MHI had to develop advanced cooling processes and materials to enable the turbines to operate at 1600C. Compared to other models available, MHI claims their J series achieves 64% efficiency when burning a 30% hydrogen mix (and 44% operating on simple cycle natural gas), whereas General Electric’s H class claims a 63% combined cycle efficiency.

As data center demand for electricity looks to explode over the coming decades (McKinsey estimates that data center power demand will grow from 25GW in 2024 to 80GW in 2030, and this may be an underestimate), and nuclear power is likely to remain very highly regulated and expensive, demand for gas generation particularly in the US is likely to grow even in a world where intermittent renewable supply increases. However, as grids in California, Texas, and New York are wracked with instability from adding too much variable energy sources, many data centers will be built off-grid and require their own electricity sources. Some data centers may be built with intermittent renewables in combination with battery backup, but the power requirements of larger data centers may outstrip the size of batteries. All of the above should mean that if MHI can continue to build efficient gas turbines, they will play a crucial role in powering future economic growth.

MHI’s pursuit of “green hydrogen” is more speculative but is a core component of Japanese energy transformation. Major Japanese car makers such as Toyota and Hyundai have hoped that hydrogen fuel will become a primary fuel source for automotive transport for decades, but in 2023, hydrogen fuel cell cars sold 0.14% of the number of Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs), and approximately 0.019% of all cars sold worldwide. Cost reductions and far greater uptake of battery-electric vehicles mean Japanese car manufacturers' bet on hydrogen fuel cell cars is unlikely to pay off.

Hydrogen does have some advantages as a fuel source compared to fossil fuels or intermittent renewables. It only emits water when combusted, does not suffer from intermittency problems inherent in wind and solar, and is already commonly produced in industrial processes to make chemical products, such as ammonia and jet fuel. However, as the smallest molecule that exists, it is prone to leakage, and given it is exceptionally flammable, it is challenging to transport. Worst of all, for widespread adoption, it uses more energy to produce than the energy the resulting hydrogen fuel stores. Cracking how to make hydrogen cheap enough to be a widely available fuel source would be a major benefit for the climate and reducing reliance on fossil-fuel producing countries.

To produce green hydrogen (hydrogen can be produced by reacting natural gas with steam at high temperatures or by using coal, which produces significant carbon emissions), water must be split in an electrolyzer, producing hydrogen and waste oxygen that can be released into the atmosphere.

MHI has built the Takasago Hydrogen Park facility to pursue research into hydrogen-fired gas turbines, hydrogen production and storage facilities. It boasts an alkaline electrolyzer with a production capacity of 1,100Nm3/h, which could produce 9,636,000 cubic meters (Nm3) of hydrogen a year. For reference, a typical gas-fired power station of 1.2MW running at 80% capacity consumes over 10 million Nm3 of natural gas per day. MHI is also pursuing the viability of using nuclear power to produce hydrogen. A 30MW research reactor in Ibaraki Prefecture is being used in a project with the Japanese Atomic Energy Agency to explore the potential for nuclear-generated green hydrogen. MHI will have to invest significant amounts of capital to see any potential return on the project, but if it is successful, it could radically change Japan’s dependence on foreign energy suppliers.

Conclusion

MHI stands as a testament to Japan's industrial prowess and technological innovation. Its diverse portfolio spanning defense, aerospace, energy, and shipbuilding has allowed it to play a crucial role in shaping the global landscape. MHI continues to demonstrate resilience and adaptability in a country with a declining population, weathering significant disruption to its nuclear energy business and previous constraints on exporting weapons.

MHI is well-positioned to capitalize on emerging opportunities in growing electricity demand, both with its existing gas turbine business and the more speculative pursuit of cheap hydrogen. If nuclear power becomes easier to build with a reduction in the amount of regulation in the US and Europe, MHI is a strong contender to export reactor designs and begin to compete with KEPCO, the South Korean energy company building cheap reactors in the UAE.

In the defense sector, if American defense planners are truly serious about building up forces and weapons stockpiles to effectively contain Chinese ambitions, the opportunities for MHI are staggering. Even if this does not come to pass, MHI will be key to strengthening the JSDF and keeping peace in the region.